Photo / Kioku Keizo

Photo / Kioku Keizo2025.01.07

Story#AgricultureArtForest

AKEYAMA: Learning About Satoyama Culture in a Hidden Region Deep in Japan

TextTaiki Honma

Photo / Kioku Keizo

Photo / Kioku Keizo2025.01.07

Story#AgricultureArtForest

TextTaiki Honma

In 2021, Tsunan Municipal Nakasu Elementary School’s Oakasawa Branch closed its doors. Now, it has been reborn as a completely new learning center: “Akeyama – Akiyamago-ritsu Oakasawa Elementary School” (hereafter, Akeyama). Dotted along the steep ravines of the Nakatsugawa River, Akiyamago is celebrated as one of Japan’s “Top 100 Hidden Scenic Spots.” Over centuries, the community here cultivated a distinct lifestyle and culture, quite unlike anything found in more accessible areas—a way of living that could be considered a blueprint of humankind’s original wisdom and cultural heritage.

Akeyama was formed to rediscover and preserve that cultural blueprint. Artists have gathered here to transform this former school into a place for exploring the region’s history and culture through art. Join us as we report on Akeyama, where the creativity of art merges with the wisdom of Akiyamago!

Midway through Akiyamago—which spans Niigata and Nagano Prefectures—lies the Oakasawa settlement. In 2021, when Tsunan Municipal Nakasu Elementary School’s Oakasawa Branch closed, it marked the end of an educational era for the settlement. From those former school buildings, Akeyama was born—a new focal point where visitors can learn about Akiyamago’s history and culture. Beginning in July 2024, Akeyama became a highlight venue for the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2024, attracting widespread attention with a variety of art installations by multiple artists. Even after the festival concluded, Akeyama continues to hold special exhibitions and workshops on a limited schedule, offering travelers ongoing opportunities to experience this singular place.

We headed to Akeyama with Mr. Hisakazu Ishizawa from the Tsunan Town Tourism and Community Development Section. National Route 405, which largely follows the Nakatsugawa River, twists sharply along cliff edges and often narrows to a single lane in places—enough to alarm unwary drivers relying on standard navigation systems.

Mr. Ishizawa surprised us by turning off the main road just beyond the Shimizukawara settlement, veering left into the mountains.

“This is technically a forest road,” he said, “but it stays wide and nicely paved, so you can drive without stress.”

Indeed, the two-lane paved forest road runs along the right bank of the Nakatsugawa, leading all the way to Oakasawa.

“People using car navigation often default to Route 405, which is why so many arrive here flustered after tackling those scary, narrow stretches,”

Mr. Ishizawa added with a wry smile.

About 40 minutes’ drive from Tsunan Town Hall brought us to the Oakasawa settlement and Akeyama. A white, reinforced-concrete building greeted us with a plaque reading “Akiyamago-ritsu Oakasawa Elementary School (※)” at the gate, alongside a sign in white letters spelling “Akeyama.” Formerly the independent Oakasawa Elementary School from 1986 to 1998—having split from Nakasukyo Elementary School Oakasawa Branch—it then became a branch of Nakasu Elementary School until being placed on hiatus in 2011, and finally closing in 2021.

(※) “Akiyamago-ritsu” is not a formal administrative district but part of the facility’s name, coined by Takashi Fukazawa—one of the artists behind the Akeyama project.

Perched atop the gateposts is a distinctive stack of firewood particular to Akiyamago. Though arranged as an art piece called “Akiyamago Tower,” it also symbolizes a defining feature of this region, where firewood is still a principal source of energy. In winter, thick snows isolate Akiyamago for extended periods, making large stockpiles of firewood crucial for survival. Locals stack the logs high in preparation for the long cold, ensuring they have enough fuel to heat their homes.

“One characteristic of Akiyamago’s firewood,” explains Mr. Ishizawa, “is that it’s cut to extra lengths, so even tall piles remain stable.”

He notes that some stacks reach nearly four meters in height. When it comes time to burn them in stoves or the traditional Japanese irori (sunken hearth), the logs are simply sawn in half to fit.

In Akiyamago, locals begin by lining the ground with stones before stacking their logs on top. In the past, they would cover the piles with thatch or cedar bark. Later came corrugated metal, and these days, a simple blue tarp is used.

“Putting stones underneath and covering the top with thatch allows moisture to escape, keeping the wood in good condition over long periods,”

explains Mr. Ishizawa. “It’s a practical technique filled with the wisdom of people who’ve lived in this region for generations.”

We then met Mr. Taisei Watanabe of the NPO Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Collaborative Organization, who helps curate and manage Akeyama. He guided us through the building. Just to the left of the entrance is the information room, with displays introducing the history of both Akiyamago and the former Oakasawa Elementary School. At the back, there is a large, easy-to-read timeline titled “The History of Akiyamago and Oakasawa Elementary School.”

Documented records of Akiyamago date back to 1321. Later, during the Tenmei and Tenpō famines of the Edo period, the community suffered heavy casualties, with several villages virtually wiped out. Around 1810, hunters from Akita (known as matagi) settled here, and in 1828, the Edo-period essayist Boku-ni Suzuki visited Akiyamago—events all noted on this historical timeline.

One striking fact is that from 1892 to 1936, while Japan was rolling out nationwide compulsory education in the Meiji era, Akiyamago was officially exempt from that mandate.

“As a remote district with limited resources, the area was simply left out,”

Mr. Watanabe observes.

“In effect, the central government pursuing modernization chose to abandon Akiyamago.”

Local residents, however, refused to give up. They became more determined than ever to ensure that their children received schooling—even if it meant sending them to neighboring villages. Thanks to this grassroots dedication, a local school finally opened in 1924.

According to the timeline, the community’s efforts culminated in 1928 with the founding of their long-cherished Oakasawa Elementary School, which stood as an independent institution and later evolved into the present-day school buildings. In many ways, Oakasawa Elementary School represents a powerful symbol of how a once-forgotten frontier fought to reclaim its place—and its children’s future—through education.

Tragically, this landmark school suspended classes in 2011, finally closing its doors in 2021. Yet from the earliest stages of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale’s development, General Director Fram Kitagawa maintained a deep interest in Akiyamago. That same year, his team began designing a new project focused on the former school building. Their goal was to transform the iconic Oakasawa Elementary School into a new hub for visitors to discover the history, culture, and natural environment of Akiyamago.

The name “Akeyama” is to derive from the word that originally gave Akiyamago its name. According to historical documents, villagers did not claim individual plots but rather practiced slash-and-burn agriculture cooperatively. Because clear boundaries were difficult to establish under this system, the people of Akiyamago embraced the notion that “land isn’t a private possession, but a collective resource,” explains Mr. Watanabe. This philosophy, woven into their history and traditions, reflects a unique perspective on how people relate to the land.

“In addition, life here demands clever ways of using natural resources in a harsh environment, far removed from the conveniences of town,” Mr. Watanabe notes. “Today we talk a lot about ‘sustainability,’ but the people of Akiyama were perfecting sustainable practices centuries ago. Kitagawa believes that their pragmatic wisdom and profound relationship with nature can inspire us to reclaim what modern society has lost.”

Kitagawa asked artist Takashi Fukazawa to direct the Akeyama project. Known for orchestrating community-based art initiatives around Japan, Fukazawa spent two and a half years—beginning in late 2021—traveling to Akiyamago for fieldwork and research that would shape his vision. “Ultimately, he identified three core themes for Akeyama: hunting, faith, and the materials and skills of the mountains,” Mr. Watanabe explains.

In his blog, Fukazawa admits, “The more I learn, the more I realize that Akiyama is far too deep for me to take on alone.” He therefore invited multiple artists, each focusing on a specific area. Aoi Nagasawa, a native of Akita Prefecture, explores hunting; Seira Uchida delves into faith; and Yui Inoue examines mountain-based materials and craftsmanship. Meanwhile, Kengo Sato of the non-profit organization Korogaro oversees the overall venue design. Additionally, works by Koji Yamamoto and Takahiro Matsuo, which have been on display previously, are showcased once again alongside their newest pieces.

Let’s head to the first floor of Akeyama to see what each room has to offer. Immediately adjacent to the information room is a booth titled “Bear Hunting in Akiyamago.” Overseen directly by Mr. Fukazawa, this exhibit displays historical materials on local bear-hunting methods and shows video footage of hunts in action.

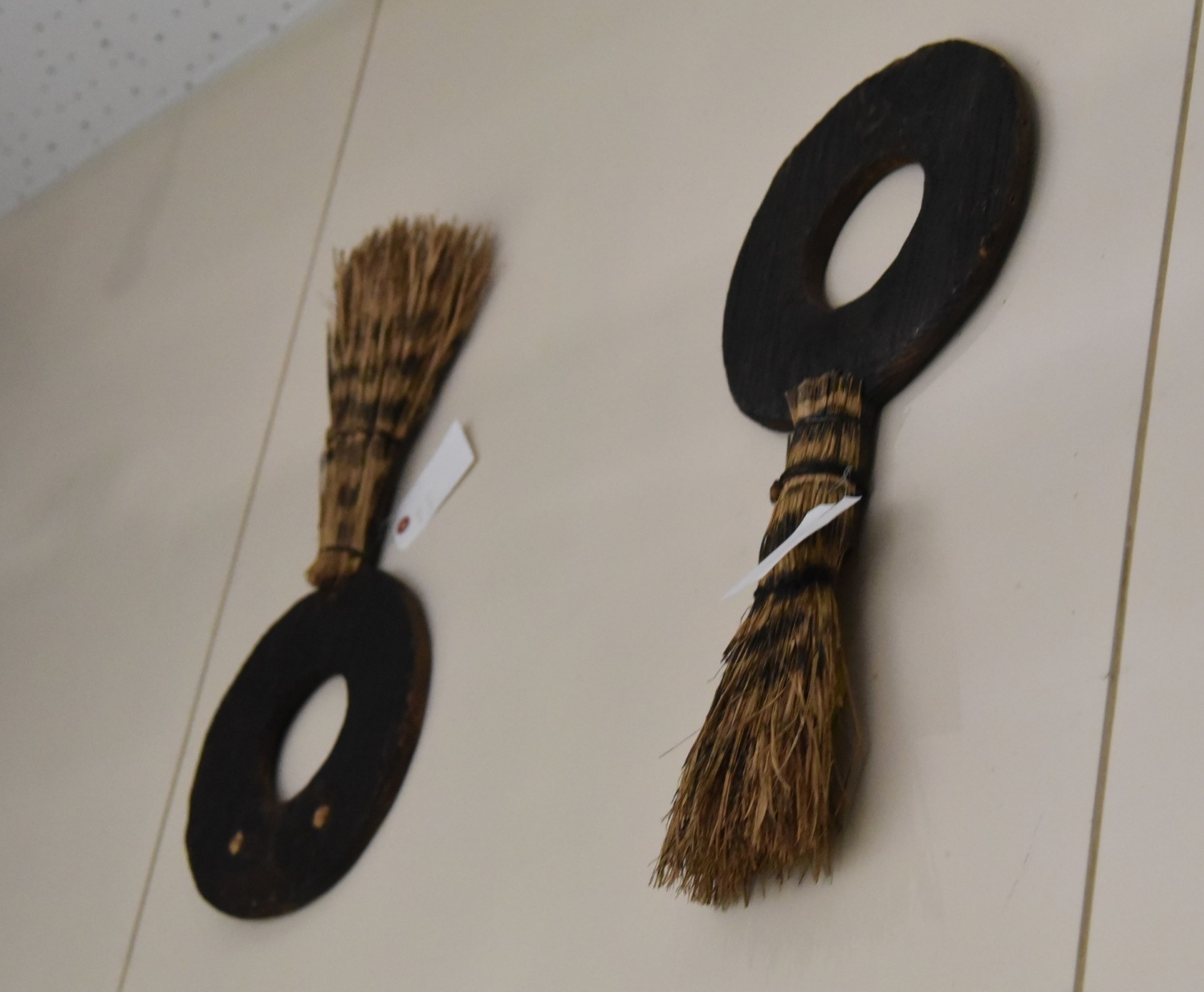

At the entrance, visitors will find a straw tool known as “Wadara,” once used for rabbit hunting.

“You would fling it up over a wild rabbit. From above, it resembled a hawk to the rabbit, causing it to dive headfirst into its burrow,”

explains Mr. Watanabe.

“Then you’d dig it out and grab its legs to catch it.”

Though once widely practiced in Akiyamago, this technique fell out of favor with the introduction of firearms.

At the center of the room is a video titled “Hiromi Taguchi’s Footage of Bear Hunting in Koakasawa.” Filmed in the 1990s by hunting researcher Hiromi Taguchi, it documents the entire process—field dressing, butchering, and even the prayers offered to the mountain gods.

“Bears have no waste; every part is used,”

Mr. Watanabe notes.

“Meat, hide, bones, and even internal organs. Locals would crush the bones, boil them, and drink the broth as medicine. The gallbladder was especially valuable, serving as a vital source of cash income for people in this region.”

Bear hunting here traces back to matagi (traditional hunters) who originally came from Akita Prefecture. In his Akiyama Kiko (Akiyama Travelogue), Edo-period writer Bokushi Suzuki records stories of these matagi settlers. They hunted and fished in remote mountain areas that even local residents seldom ventured into, journeying all the way to Kusatsu Onsen to sell their catches along the route. According to their accounts, the breathtaking highland landscapes they passed through—even more secluded than Akiyamago—surpassed anything most people would imagine of this so-called “hidden region.”

Venture further inside, and you’ll find a display by artist Koji Yamamoto, who has been developing his Phlogiston series of charcoal sculptures in the Echigo-Tsumari region since 2006. His striking works—carbonized carvings made from local species such as horse chestnut and alder—command a powerful presence, each piece revealing the character of the surrounding forests.

In a small adjoining room, Yamamoto’s new creation, “Kyōchū Sansui: Akiyamago Scene,” is on exhibit. He grinds mulberry, horse chestnut, alder, and birch from the Akiyamago area into charcoal pigment, then paints a panoramic landscape of Akiyamago across the left and right walls.

“He’s depicted Naeba Mountain to the east, across the Nakatsugawa River, and Torikabuto Mountain to the west,”

explains Mr. Watanabe.

“Notably, Yamamoto continued adding to the mural during the exhibition itself. Whenever he came to Akeyama, he’d paint more—sometimes alongside visitors who happened to be there.”

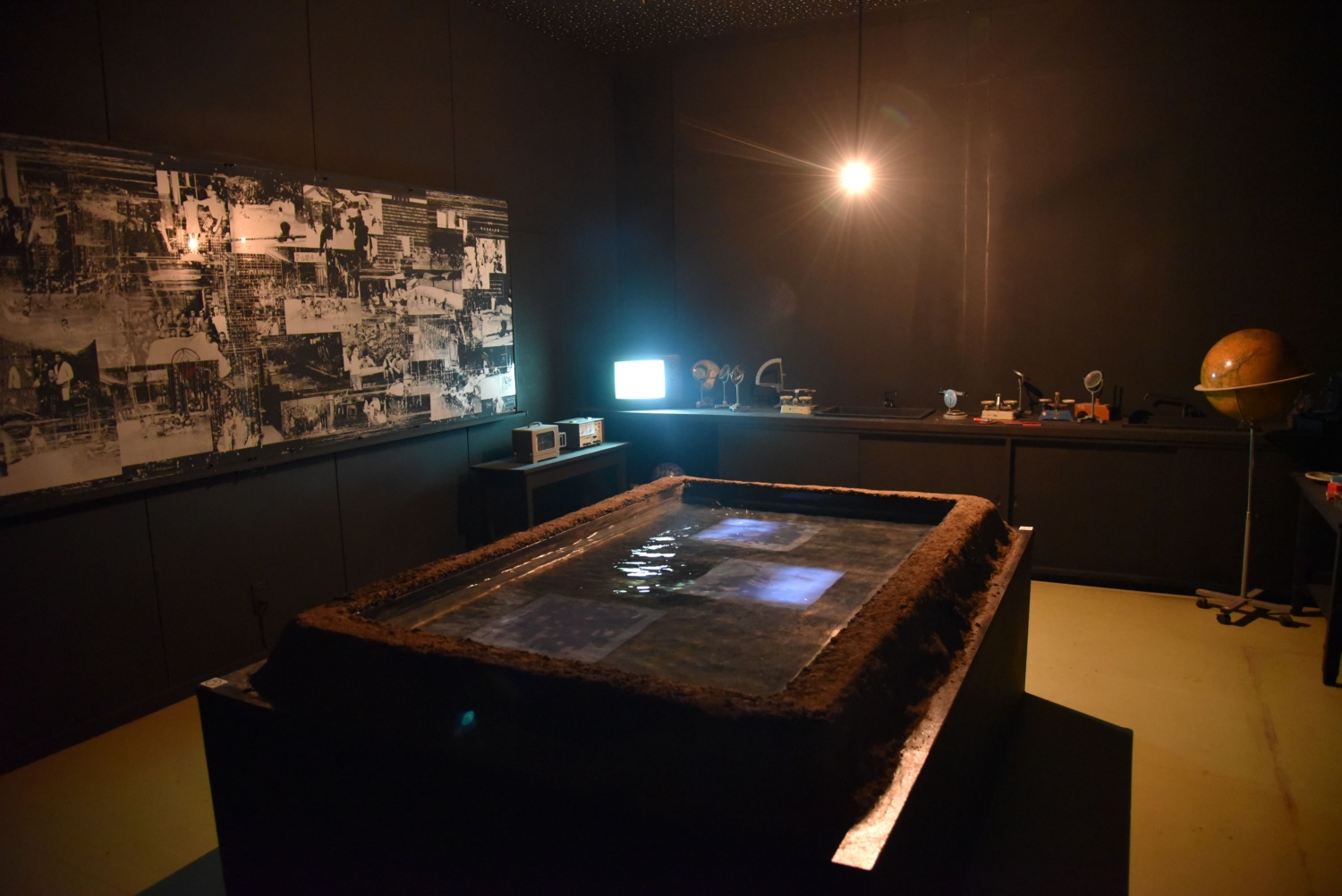

Next door is Takahiro Matsuo’s “Pool of Memories.” In the center of this dimly lit room, you’ll see a rectangular, earthen-walled structure resembling a water tank. Modeled on a hand-built swimming pool that once existed at Oakasawa Elementary School, it pays homage to the creativity of local adults who, at a time when the school had no pool, compacted earth to craft one for the children. Matsuo discovered a photograph from 1971 showing the original pool and recreated it as a testament to the community’s resourcefulness and dedication to its youth.

“I’ve spoken with people who actually swam in that homemade pool,”

says Mr. Watanabe.

“They remember how cold the mountain spring water was, even in summer.”

Though the water may have been chilly, the warmth of the grown-ups’ hearts surely made its mark. Dozens of photographs of smiling children at play around the pool line the walls, capturing a cherished piece of local history.

(Note: Takahiro Matsuo’s “Pool of Memories” is no longer on public display.)

Climb the stairs to the second floor, and you’ll notice several softly illuminated photographs on either side, reminiscent of traditional lanterns. This installation—another of Mr. Fukazawa’s works—is titled

“Folk Tools and Family Photos from the Yamada Heiji Home in Mikura.”

In 2020, Mr. Heiji Yamada of Mikura settlement passed away, leaving behind a 200-year-old house filled with folk artifacts, furniture, and tools. His father, Shigeyoshi, had owned a camera, capturing countless scenes of everyday life in Akiyamago during Japan’s nostalgic Shōwa era. Those images are now gathered and displayed along the staircase, offering a rare glimpse into the vibrant lives of the region’s residents decades ago. One photo even shows a charming bear cub alongside local villagers—a poignant reminder of how intimately people here once lived with nature.

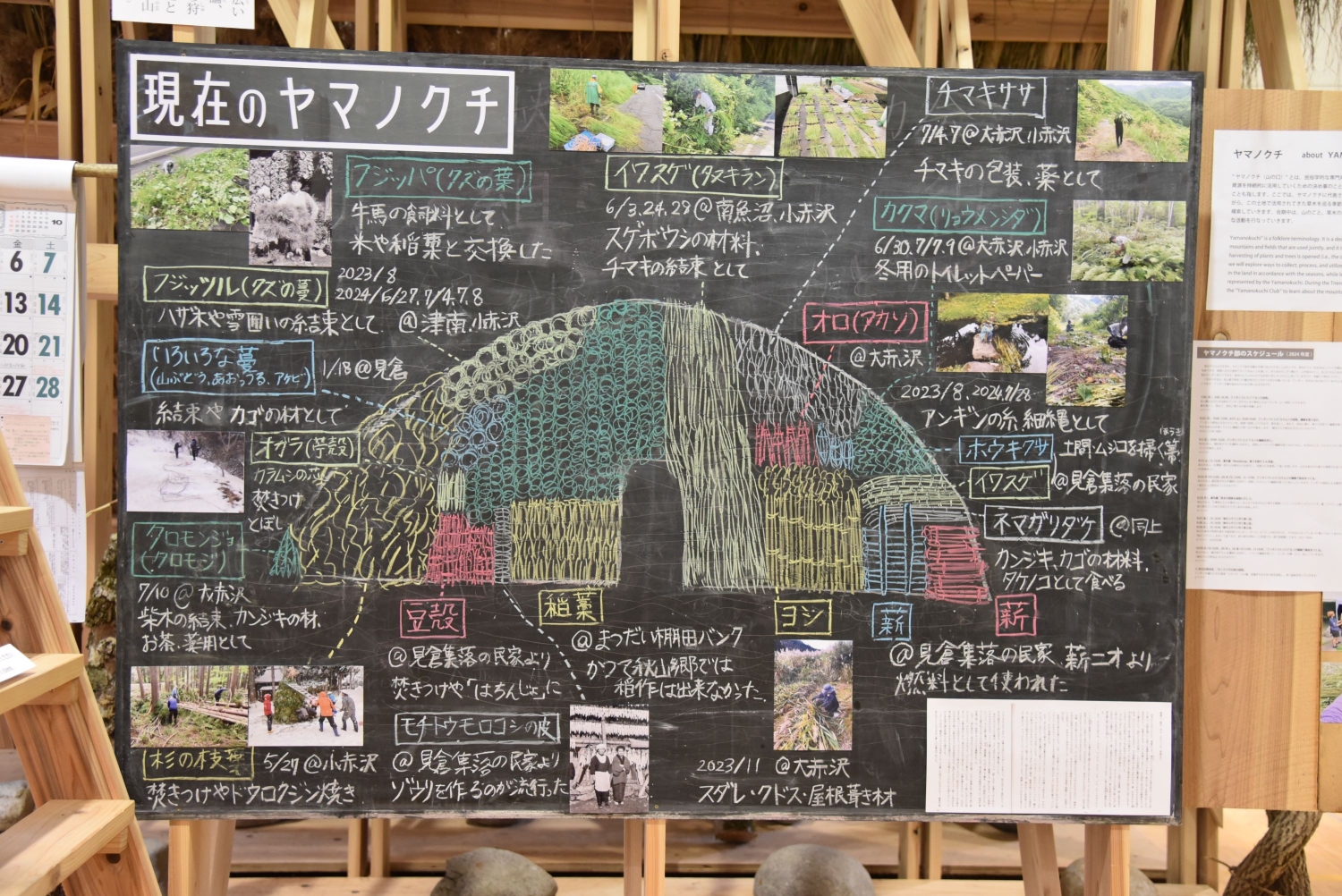

Ascending to the second floor, you’re immediately greeted by a massive exhibit known as “Yamanokuchi.” Artist Yui Inoue—who notes that “in Akiyamago, the mountain itself was both a place to live and the raw material for life”—has recreated the “mountain” setting indoors. Spanning roughly 15 meters in width and rising 6 meters high, its lattice frame is densely packed with plants gathered from the Akiyamago region: rice straw, reeds, ogara (dried stems from sweet potatoes), oro (also known as akaso), iwasuge (a type of sedge), and more. Historically, each of these botanical resources has been vital to daily life in Akiyamago, a place often short on manufactured goods.

“Here in the mountains, where modern conveniences are scarce, people have relied on seasonal vegetation for centuries,”

says Mr. Watanabe.

Firewood is an invaluable fuel source; oro (akaso) can be boiled and pounded to extract fibers spun into thread for clothing, called angin. Various vines become makeshift ropes, nemagari-dake bamboo is fashioned into snowshoes and baskets, hōkigusa (broom grass) is turned into brooms, and ogara (dried potato stems) serves as tinder.

The name “Yamanokuchi” is derived from the local custom of opening the mountains—literally “mountain mouth”—for communal gathering on designated days. This shared tradition ensures the sustainable use of mountain resources and reflects a deeper wisdom about living with nature. By naming the work “Yamanokuchi,” the artist underscores a desire to revive this vital knowledge—once integral to human life yet largely forgotten in the modern era.

One of the most striking installations on this floor is “Kamagami-sama-tachi no Ochakai: Stories from the House of Faith,” created by Seira Uchida. In this imagined “House of Faith,” inhabitants learn from the mountains about exorcisms and memorial rites, while supernatural figures called Kamagami-sama gather for a tea party. Although whimsical, the piece is based on real customs that once flourished in Akiyamago, meticulously researched and revived for this exhibit.

In the back room, you’ll find futons laid out on the floor and two hanging scrolls suspended in the tokonoma (alcove). During Akiyamago’s long winters, deep snow often prevented doctors or Buddhist priests from reaching these remote villages. Locals developed their own rites to heal the sick or ease someone’s final moments, sometimes using special scrolls—like Kurokoma-Taishi—held over the patient’s body as they prayed. This exhibit replicates those winter rituals that could only have emerged in an isolated, snowbound environment.

Everywhere you look in a traditional Akiyamago home—at the hearth, in the kitchen, near the entrance, or even the toilet—tiny household altars and protective talismans can be found. Faith and ritual weave through everyday life, and in particular during New Year’s celebrations, families place rice cakes in the cooking pot, decorate them with branches, and observe other customs rarely seen elsewhere. Uchida’s installation recreates this spiritual tapestry, offering a vivid glimpse into Akiyamago’s distinctive worldview.

In the center of the second floor stands a white, dome-like structure with a narrow entrance that only allows one person to crouch down and pass through—somewhat reminiscent of an igloo. Historically, the matagi hunters who traveled from Akita would roam the vast interior mountains and take breaks in caves known as “Ryū.” Artist Aoi Nagasawa has drawn inspiration from these caves for her piece, “Yama no Hara” (“Mountain Belly”).

Upon entering, you discover a surprisingly spacious area, reminiscent of a real cave. A small irori (hearth) sits at the far end, surrounded by mats similar to woven straw mushiro. In days past, the matagi had strict rules while hunting, including one forbidding any talk of village life in the mountains. Within such remote terrain, an entirely different sort of time and narrative held sway—disturbing it was off-limits. One wonders what stories they must have shared inside their cave sanctuaries.

Before creating this exhibit, Nagasawa and the Akeyama team decided to visit an actual Ryū used by local hunters, a place known as “Bōzawa no Ryū” on the far side of Mt. Naeba. Though it was April, the area was still buried in snow.

“Even though I left Ooakasawa early in the morning, the path was treacherous and I hadn’t arrived even by evening. Night fell, visibility disappeared, and I had to camp outdoors. Then it started snowing as well. The next day I managed to reach a ski resort’s lift station nearby and was somehow saved,” they told me.

He notes that in years gone by, locals could apparently hike to the Ryū and back in a single day—a testament to their extraordinary physical endurance.

Another must-see is a small booth in the rear right corner of the second floor:

“The Intertwined World of Work and Play in the Life of Masamichi Yamada.”

Born in 1952, Yamada-san is currently the sole resident in Mikura. He learned hunting from the late Heiji Yamada, venturing with him into the winter mountains. Yamada-san still uses the traditional wadara method for catching rabbits, perhaps the only person in Akiyamago who does so.

Despite depopulation and the fading of old community events, Yamada faithfully carries on the region’s customs and ceremonies—those long observed at the New Year and “Little New Year,” among many other traditions.

The late folklorist Shūichi Takizawa once noted that practices like wadara hunting illustrate how “livelihood and play” blended seamlessly in Akiyamago’s way of life, which was founded on harvesting nature’s bounty. Work wasn’t something grim; it was infused with enjoyment, becoming living knowledge and a source of joy. In this booth, a video shows Yamada-san in the snowy mountains hunting rabbits, looking very much as though he’s simply at play.

In addition to these highlights, you’ll find more exhibits throughout Akeyama. One is “Yukiko Hirota’s Democracy and Angin,” which showcases Hirota’s research on a weaving technique called angin—using fibers from akaso—handed down in her home settlement under the guidance of Takizawa. Her successful revival of this technique takes shape through an installation.

Also on display is “A Volcanic Stone Presented by Korean Laborers to the Fujinoki Saka Family, or Possibly a Memorial,” a volcanic rock offered by Korean laborers who worked on the Nakatsugawa Hydropower Plant construction during the Taishō era. These individuals, pressed into hard labor during Japan’s modernization, were not few in number. In gratitude to the Fujinoki Family, who provided them lodging free from discrimination, the workers carried this stone—dozens of kilograms’ worth—on their backs from the construction site. By exhibiting it today, Akeyama reminds us of another chapter in Akiyamago’s history and the complexities and contradictions of modernization.

Adjacent to the “A Continued Akiyama Travelogue” editorial room, you’ll find a resource room with an array of books, documents, and footage of daily life in Akiyamago. A vintage rotary phone lets you hear audio recordings as you watch video clips of different local customs.

Because Akiyamago is so remote, it retains memories and traditions that have vanished elsewhere. These hold vital messages for our modern world, saturated with technology and driven by market forces: Don’t exploit nature but share and use it sustainably; revere the unseen forces and respect their presence; and nurture simple faith to face the challenges of a harsh environment.

Akeyama conveys these ideas not through rigorous academic study, but via the approachable lens of art. Alongside the exhibits, practical workshops are held where participants can discover the history and customs of Akiyamago. Each artist imparts insights gleaned directly from this region.

From July to November this year, workshops included “Making Mini Kamagami-sama” and “Experiencing Akiyama Faith” (by Seira Uchida), “Story-Making Inside the Mountain Belly” (by Aoi Nagasawa), and “Walking and Measuring Akiyamago” (by Kengo Sato). As part of a live art program called “Yamanokuchi-bu” (led by Yui Inoue), visitors could try their hand at weaving angin or exploring forests to gather natural materials like kozawashi. Furthermore, symposiums and talks were organized with British social anthropologist Tim Ingold and Japanese historian Satoshi Shirouzu to envision the future of both Akeyama and Akiyamago in partnership with local communities.

Ultimately, Akeyama serves as a “modern school” for people today—showcasing Akiyamago’s nature, way of life, history, and culture, while reminding us of the vital, perhaps forgotten values that shaped human societies for generations.

TextTaiki Honma

ForestGeography

Walk Amid Spectacular Views of the Naeba Foothills and Akiyama-go!

TextTaiki Honma

AgricultureWaterSnow

The Story of Tsunan’s Water

TextMatt Klampert

PeasefulForestGeography

A Look into the Calming and Peaceful Forests of Tsunan

TextMatt Klampert

AgricultureWaterGeography

The Water of Ryugakubo──The Wonder of Nature and the Deity

TextTaiki Honma

©2025 Tourism Tsunan